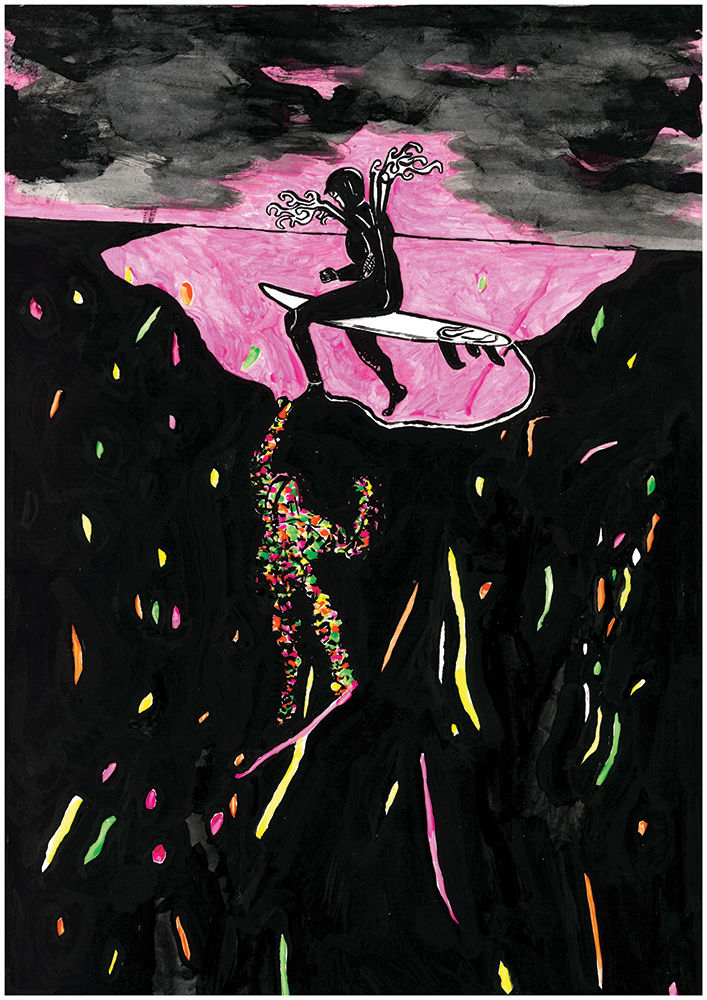

Ben Cook, You Should Have Been Here Yesterday

Site-specific, hand painted wooden sign

From the 'A Frame' series, 2012

Creative Contagion/ Catching Sea Fever

Lizzie Perrotte, February 2024

‘We hurry to catch the tide or catch something’ (Bloomfield, 2023)

Last October I caught a sea fever (more of a shimmer than a shiver) and I discovered something rich and strange in its delirium. Flotsam and jetsam of memories, sensations, and wild thoughts have now washed up from the experiences of Sea Fever 2 (2023), a SolasArt pop-up exhibition, curated in the Borlase Smart studio, overlooking Porthmeor Beach, St Ives in Cornwall. This exhibition, entwined work by four creatives, three visual artists and a poet; all surfers and eco-critical thinkers based in the South West of England. One premise of the show was to reflect on a surf art project organised over 30 years ago as part of the launch programme of Tate St Ives in 1993. That project invoked the title of John Masefield’s poem, Sea-Fever, giving it a new toxic twist for the 20th century’s closing decade.

Masefield’s Sea-Fever was originally presented in his collection of Salt Water Ballads published in 1902 at the height of Britain’s maritime empire. An experienced sailor, Masefield made several references to sea fevers in this collection. A couple of the poems represent the fever as a symptom of a deadly disease, a form of capitalist contagion that was contracted and transmitted globally aboard colonial vessels. However, Masefield also celebrated sea fever as an intense mode of desire, an all-consuming masculine fantasy, a yearning for an altered state of consciousness. Through sea fever he could become unbound, open to a relational mode of perception which was in tune with “the call of the running tide”, “the gull’s way” and “the whale’s way” (Masefield, 1923, 28).

“We will have been here yesterday” (Bloomfield, 2023)

Back in 1993, we conceived the Sea Fever project as a form of soft institutional critique, a critical intervention within Tate St Ives’s first collection displays of Modernist works. The museum’s historical narrative was, at that time, dominated by revered artists such as Barbara Hepworth, Peter Lanyon, Patrick Heron and Terry Frost who made abstract work in dialogue with the dynamics of their coastal environment. Co-curated by Lizzie Perrotte from Tate and visiting artist-in-residence Andy Hughes, Sea Fever (1993) was a vibrant, unruly, participatory programme of events and workshops that opened the museum to fresh conversations with Cornwall’s surfing community and environmental activists. Events for Sea Fever (1993) involved collaborations with Surfers Against Sewage, a marine conservation charity that had been recently created in 1990 by Cornish surfers. The project celebrated the creative alterity of a local surfing culture and the visionary potential of surfing sea fever. Surfers brought alternative knowledge of the ocean environment through an expanded consciousness and unique phenomenology. They also brought a new critical perception of environmental predicament and a strong motivation for political activism. However, in 1993 local Cornish newspaper articles were dominated by celebrations of Tate’s arrival, welcoming its powerful agency as a commercial catalyst of cultural tourism in the county. These were interleaved with short but regular notices about ongoing sewage leaks into the sea. There were only curt references to the powerful groundswell of environmental protest and activism against ocean pollution.

“capital triumphs, cornucopia prevails, waste rules” (Bloomfield, 2023).

Thirty years on, in 2023, life goes on in a “vast foggy lethargy” and “grey-green inertia that embraces us all” (Bloomfield, 2023). Sewage, chemicals and waste matter continue to be dumped into the sea in Cornwall despite a level of popular consciousness of an irreversible climate change that has triggered rising sea levels and terrifying escalation of ocean pollution with catastrophic death of marine life. It has become apparent how far the surfing industry is complicit in the capitalist contagion of sea fever. By generating fantasies of freedom, it stimulates the desire for consumption through tourism, fashion and sports equipment, much of which is still produced using highly toxic materials and ocean pollutants. Through Shored (2023), a collage prose poem presented as a sound installation in the exhibition, Bloomfield figures this capitalist contagion as a “tentacled monster that has spun its sticky web over the wide blue waters for centuries”. She asks: “If we struggle, do we only teach it better ways to suck us dry? (Bloomfield 2023). Political economist and ecocritical thinker, Jason Moore, has proposed that “power, production and perception” are always entwined and that our current environmental crisis is profoundly related to a crisis in perception. Our existential predicament requires a new sensorium and a new relational language to envisage the shifting dynamics of a planetary web of life (Moore, 2015).

Elizabeth Perrotte introducing guest speaker Sam Bleakley, 2023

Sea Fever 2 (2023) manifested the sinister presence of Bloomfield’s tentacled monster, this capitalist contagion with its rhizomatic extensions and deadly entanglements. It appeared in various guises as a toxic foe in large psychedelic drawings by environmental activist, Captain Banplastic, a mysterious mutant, posthuman surfing superhero. It loomed, shimmered and shape-shifted in photographs and film works by Andy Hughes that heightened attention to the seductive posthuman power and monstrous agency of plastic waste matter. Through Shored (2023), Bloomfield’s lyrical, mesmeric yet critical voice flowed through the exhibition space, seeming to move in conversation with the tidal flows of the nearby Atlantic Ocean. Salvaged words and fragmentary images that were dredged from literary sources such as Masefield, Walt Whitman, T.S. Eliot, Virginia Woolf and academic books on ecology, waste and poetry, became mingled with shreds of conversation or advertising and Bloomfield's own writing. They swirled around the gallery space entangling works of visual art like “washed-up drift” (Bloomfield, 2023). Bloomfield questions whether the “wild call’’ of Masefield’s Sea-Fever can still be heard now that the sea is known to be a “sink for waste” and is no longer “vast enough for dispersal into oblivion”. Our yearning for something pure and wild is troubled by a morass of cultural waste matter; the debris of a capitalist and colonial past that keeps washing up all over. “If Poetry can’t save us” and “Art won’t change the world”, what, Bloomfield asks, “is possible in the wake of catastrophe?”. “Can we move out of mind into the more than human world?” (Bloomfield, 2023).

“Pink and green, pink and green and sheen. Pink, pink, pink, high on chrome” (Bloomfield, 2023).

Last October I caught a sea fever in the SolasArt exhibition but discovered a creative potential in its delirium. Coming together in that small studio space on the edge of the Atlantic, the works of art shimmered with uncanny, psychedelic affects as though an aesthetic contagion was passing through them. In different ways, each of the works defamiliarized habitual modes and tempos of perception. Verging on the hallucinatory, Ben Cook’s small, intensively focussed drawings of surfers’ pathways from car parks to the beach, force an obsessive gaze on the mundane and overlooked. Hughes’s photographs and film animations using low angle, extreme close-up and intense colour, disorientate scales of time and space to amplify the presence and agency of plastic mattering in the ocean. These works stimulate unaccustomed levels of attunement to things beyond our current bounds of understanding, things philosopher Timothy Morton terms ‘hyperobjects’ (Morton, 2013). The works of art gathered in Sea Fever 2 (2023) disorientated and heightened my senses, confusing taxonomies of matter or measurable markers of time and scale. The creative contagion generated between the works stalled rational interpretation, and stimulated enchantment, opening me to a state of unknowing. Catching a sea fever gave me a moment of hope that visual artists embracing such radical aesthetics can help to transform perception, cultivate more relational modes of thinking and help us embrace the alterity of more-than-human forces intra-acting in a planetary web of life.

References

Bloomfield, M., (2023) Shored, prose poem/sound installation

Masefield, J. (1923) The Collected Poems of John Masefield. London, William Heinemann Ltd.

Morton, T. (2013) Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology After the End of the World. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Moore, J.W. (2015) Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital, London and New York: Verso.